U.S. MARSHAL

INFORMATION

Founded in 1789, the United States Marshal Service or USMS, and by extension its agents, has long been an enforcer of federal law across America. All ninety-four sectors are headed by a marshal, appointed by the president himself - leading and commanding a number of Deputy US Marshals under them.

Only one U.S. Marshal may exist in the Lavinian sector at one time - as such an important and wide-reaching role, it is expected that the player of the U.S.M. is an active member of the community.

REQUIREMENTS

U.S. Marshals are considered a restricted-opportunity. Characters must be African-American or Caucasian to apply, and must additionally be male in respect to historical accuracy.

BENFITS

-

Base Paycheck of $16.00

-

Access to player bounties

-

Access to NPC bounties

-

Right to enforce federal laws

GUIDELINES

Only one U.S. Marshal may exist in the Lavinian sector at one time - and may in turn hire up to two deputies to help them manage the region. U.S. Marshals have the right to handle all federal crimes, but may not interfere with local law enforcement unless directly invited or witnessing the crime.

A certain degree of realism and proper portrayal is expected in the roleplay of a U.S. Marshal - a detailed guide of integrating realism into your roleplay is listed below.

Corruption will not be allowed for this career.

ROLEPLAYING A U.S. MARSHAL

The United States Marshals Service, established in 1789, is the oldest federal law enforcement agency in the country. By 1885, a U.S. Marshal was not just another frontier lawman — he was a federal officer tasked with upholding the authority of the U.S. government across vast and often lawless territories.

Unlike local sheriffs or town constables, a Marshal didn’t answer to voters or regional politics. His job was to enforce federal law, carry out orders of the federal courts, and maintain justice on a larger scale.

Marshals and their appointed Deputy U.S. Marshals served a wide range of duties, including:

-

Apprehending federal fugitives

-

Serving subpoenas, warrants, and writs from federal courts

-

Guarding and transporting prisoners

-

Handling asset seizures and auctions

-

Conducting executions (in federal cases)

-

Breaking up illegal distilleries and enforcing federal revenue laws

In rougher regions — especially the western territories — a U.S. Marshal might be the only meaningful arm of the federal government. These men traveled light, worked dangerous beats, and often operated alone or with just a few Deputies. While sometimes mistaken for bounty hunters or gunslingers, a Marshal’s badge carried legal authority, not freelance justice.

Roleplaying a U.S. Marshal or a Deputy U.S. Marshal means stepping into the boots of a serious and sworn federal agent - someone caught between the courthouse and the gunfight, between dusty trails and the growing power of federal law. As such, the role is not to be taken lightly, and must be properly portrayed to avoid revocation.

JURISDICTION

Unlike sheriffs or policemen, a U.S. Marshal abides by federal jurisdiction - thus under the authority of the government rather than state-by-state institutions. In 1885, a Marshal’s reach extended across entire judicial districts — often encompassing multiple counties, and in some cases, entire territories. These districts were defined by federal circuit and district courts, not state lines or municipal borders. For ease of roleplay, the entirety of the State of Lavinia encompasses one district.

Marshals were responsible for enforcing federal law only — they had no direct authority over state or local crimes unless those matters interfered with federal interests. Their duties included serving federal arrest warrants, subpoenas, and writs; apprehending federal fugitives; and supporting federal judges, especially during circuit court proceedings. In regions like Indian Territory, where state authority was limited or nonexistent, Marshals often became the default lawmen, acting as the sole representatives of U.S. legal authority.

However, Marshals did not patrol or “ride circuit” like a local peace officer might. Their actions were warrant-based, and while they could cross county lines and even state borders in pursuit of a federal fugitive, their authority was tied strictly to federal cases. If a Marshal intervened in a local matter, it was likely because it touched on interstate crime, federal land, revenue law, or a violation of constitutional rights. Jurisdiction was a matter of law, not convenience — and those who misunderstood it often found themselves overstepping, or worse, being accused of abuse of power.

DUTIES & RESPONSIBILITIES

The U.S. Marshal was the chief federal law enforcement officer within a judicial district, acting as the enforcement arm of the federal courts. Unlike local lawmen, Marshals did not handle everyday crime unless it involved federal law. Their role combined law enforcement, judicial support, and administrative work.

1. ENFORCE FEDERAL LAW

-

Execute arrest warrants issued by federal judges or commissioners.

-

Pursue and apprehend federal fugitives.

-

Investigate crimes in areas under exclusive federal jurisdiction (e.g., Indian Territory, mail routes, federal land).

-

Suppress insurrections, riots, or violations of federal law (e.g., illegal whiskey trade in Native lands).

2. SERVE THE COURTS

-

Serve summonses, subpoenas, and writs.

-

Enforce civil orders, such as property seizures, foreclosures, or injunctions.

-

Collect court fines, fees, and judgments.

-

Deliver court documents across wide territories.

3. TRANSPORT AND GUARD PRISONERS

-

Escort prisoners to and from jails, courts, or prisons—sometimes over hundreds of miles.

-

Guard courtrooms, juries, and judges.

-

Arrange lodging and meals for long-distance prisoner hauls (often on horseback, wagon, or train).

4. FORM POSSES AND DEPUTIZE

-

Organize posses when facing resistance, armed fugitives, or dangerous territory.

-

Deputize trustworthy men (temporarily or long-term) as Deputy U.S. Marshals to assist with duties.

5. ADMINISTRATIVE DUTIES

-

Keep records of arrests, expenses, miles traveled, and actions taken.

-

Submit detailed reports and receipts to the Department of Justice to receive reimbursement.

-

Handle logistics and budget for deputies, guards, and prisoner movements.

RANKING & APPOINTMENT

The U.S. Marshals Service didn’t operate with formal military-style ranks, but the structure included a few key roles, mostly based on appointment and delegation of authority:

1. U.S. MARSHAL

-

Appointed directly by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

-

Held the highest authority in a federal judicial district.

-

Served a 4-year term but could be replaced at any time.

-

Answered to the federal district court and enforced its orders.

-

Oversaw hiring, budgeting, and supervision of deputies.

2. DEPUTY U.S. MARSHAL

-

Hired directly by the Marshal.

-

Carried out day-to-day law enforcement: arrests, prisoner transport, posse formation, warrant service, etc.

-

Paid by fee system (not salary)—they earned money per job (e.g., per arrest, per mile for transport).

-

Could be temporary or long-term, depending on workload and trust.

3. SPECIAL DEPUTY U.S. MARSHAL

-

Sworn in for specific tasks or emergencies (e.g., manhunts, riot control, guarding juries).

-

Might be local men, former soldiers, or scouts hired as needed.

-

Often received the same authority but only for a limited time or mission.

Note: There was no "Chief Deputy" title codified in this era, but marshals often had a trusted lead deputy in practice.

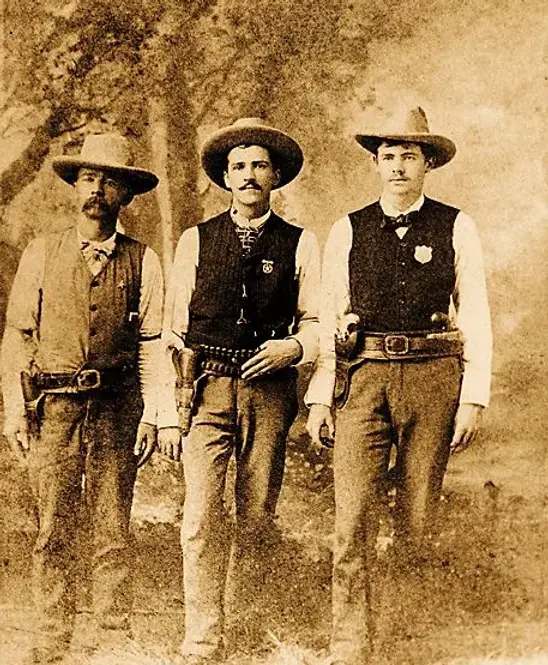

PRESENTATION & ATTIRE

A U.S. Marshal in 1885 would have presented himself not as a flashy figure, but as a practical, authoritative man of the law, shaped by the demands of his district—whether it be the muddy frontier, a Southern city, or Indian Territory. There was no official uniform, and marshals were responsible for supplying their own clothing and gear. As such, their appearance leaned heavily on regional norms, personal taste, and the need for durability.

CLOTHING

-

Shirt: Plain or striped cotton shirts, sometimes with detachable collars. White was less common due to dust and wear.

-

Trousers: Wool or heavy cotton, often suspenders instead of belts. Earth tones and greys were common.

-

Coat or Vest: A waistcoat (vest) was typical, and for fieldwork or cooler months, a long duster or sack coat was worn. In colder regions, canvas or buffalo-hide coats were used.

-

Hat: Wide-brimmed felt hats (e.g., slouch hats, derby/bowler hats, or early Stetsons) were common. The style depended on climate and taste, not a fixed "marshal" look.

-

Footwear: Sturdy leather boots or brogans. Spurs were uncommon unless riding frequently.

GEAR

-

Sidearm: Most carried a revolver—typically a Colt or Smith & Wesson—worn in a hip or cross-draw holster. Double action was becoming more popular by the mid-1880s.

-

Rifle or Shotgun: Often kept for serious work like prisoner transport or posses. A Winchester rifle or double-barreled shotgun would be typical.

-

Badge: Many marshals did not wear a badge at all. If they did, it was often a small star or oval pinned inside the coat or displayed only when needed. Some used paper commissions instead.

-

Other items: Pocket watch, small ledger or warrant book, handcuffs or manacles (though not always carried), and sometimes a pocket Bible or personal item.

GROOMING & DEMEANOR

-

Beards and mustaches were common, though some kept a clean shave.

-

Hygiene varied, but marshals representing federal law were expected to appear orderly, clean, and composed, especially in court settings.

-

Demeanor ranged from quiet and professional to tough and commanding—many marshals walked a line between official restraint and the rough practicality needed to deal with outlaws.

ETHICS & MORALS

While many imagine U.S. Marshals of the 1800s as paragons of justice, the truth is more complicated. These men were federal enforcers in a time when law and morality were often shaped by politics, prejudice, and power. A marshal might arrest a man for stealing a horse one day, then forcibly remove Native families from their land the next—all under the same banner of federal authority. Ethics weren’t always clear-cut; what was legal wasn’t always just, and marshals had to decide where they stood when duty conflicted with conscience.

Some marshals, like Bass Reeves, earned reputations for fairness, restraint, and courage in the face of corruption and racism. Others exploited their power, profiting off prisoner transport, abusing their authority, or turning a blind eye to local injustices. In the absence of strict oversight, a marshal’s personal code often mattered more than official policy. Whether they upheld the law with honor or used it as a shield for self-interest, their choices reflected not just federal will—but the moral grey zones of a growing nation.

Within roleplay, we do require non-corruption from our marshals, to ensure a fair federal force across the server. Personal prejudices are allowed, but marshals and deputy marshals are obligated to remain fair and non-biased in order to keep a level playing field.

HISTORICAL FIGURES

GROVER CLEVELAND

Born in New Jersey and raised in New York, Grover Cleveland rose from small-town lawyer to the 22nd President of the United States, taking office in 1885. A Democrat known for his plainspoken manner and fierce opposition to political corruption, Cleveland represented a shift toward integrity and restraint in a government still adjusting to life after Reconstruction. His belief in limited government was balanced by an insistence that federal law be upheld without fear or favor.

During Cleveland’s first term, the United States Marshals Service continued to serve as the muscle of federal authority, particularly in regions where state and local law had faltered or grown too entangled in partisanship. Marshals were instrumental in enforcing election laws, pursuing federal fugitives across state lines, and supporting federal courts in areas where resistance was common — especially in the South and the West. Cleveland’s appointment of Augustus H. Garland as Attorney General further strengthened the legal foundation of the Marshals’ work, emphasizing lawful procedure and constitutional order.

Though Cleveland’s administration is often remembered for its vetoes and its caution, his steady reliance on the Marshals Service reflected a core truth of his presidency: that law and justice must remain above political gamesmanship. Whether enforcing tax rulings or guarding courtrooms, the Marshals under Cleveland’s watch continued to serve as the quiet backbone of federal justice — upholding authority not with spectacle, but with resolve.

AUGUSTUS H. GARLAND

Born in Tennessee and raised in Arkansas, Augustus H. Garland came of age in a divided nation, serving in the Confederate Congress during the Civil War. A staunch Southerner turned postwar unifier, Garland returned to public life during Reconstruction and ultimately rose to become a trusted statesman and legal mind within the federal government.

In 1885, Garland was appointed Attorney General of the United States by President Grover Cleveland. His tenure marked a pivotal moment in the postbellum South’s reentry into federal influence. As the nation’s chief legal officer, Garland oversaw the Department of Justice during a time of expansion — a period when federal lawmen, including U.S. Marshals, found themselves confronting everything from political corruption to western lawlessness.

Garland’s time in office was not without controversy. Most notably, he became entangled in the Bell Telephone cases, wherein he was accused of improperly using his position to advance interests he’d been involved with before taking office. Though eventually cleared of wrongdoing, the episode was a reminder of how closely the Department of Justice had become tied to economic power and the growing pains of modernization.

BASS REEVES

Born a slave in Arkansas, Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves lived through the Civil War first-hand. Having allegedly escaped from his bondage sometime between 1861 and 1862, after attacking his Confederate slaver over a game of poker, Reeves fled into Indian Territory, becoming familiar with the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole.

Reeves returned to Arkansas a free man after the Civil War's end, farming until 1875. Marshal James F. Fagan, directed to procure two-hundred deputy marshals, hired on Reeves at the age of 37, among the first black men to serve in the position and easily one of the most famous for his connections to Indian Territory and his understandings of the local cultures therein.

Though his story did not end in the 1880s, with Reeves going on to transfer his services to Texas and later to serve on the Muskogee Police Department, his tale would no doubt be a widespread one in the United States Marshal Service, especially among deputies within the southern states. Reeves and his history serve as a firm reminder of what the USMS have and will always represent - fair opportunity based on skill, connections, and ability rather than prejudice and hatred.

JUDGE ISAAC C. PARKER

Oftentimes known as the "Hanging Judge, Isaac Parker was a notorious figure in the United States south during the 1800s. The first United States District Judge of Arkansas - and by extension the overseer of the adjoined Indian Territory - Parker was a ruthless upholder of the law and a well-known figure. In over 13,490 cases, more than 8,500 were convicted under his watch - and 160 sentenced to death.

Though perhaps not the most beloved of judicial representatives, most marshals would know of or have met the man if they work south of Arkansas. By that extension, he is a good model of what the courts looked like and favored in terms of federal cases in the late 1880s.